Chainalysis Detects Significant Wash Trading and Some Money Laundering In this Emerging Asset Class

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) were one of the biggest stories in cryptocurrency in 2021.

NFTs are blockchain-based digital items whose units are designed to be unique, unlike traditional cryptocurrencies whose units are meant to be interchangeable. NFTs can store data on blockchains — with most NFT projects built on blockchains like Ethereum and Solana — and that data can be associated with images, videos, audio, physical objects, memberships, and countless other developing use cases. NFTs typically give the holder ownership over the data or media the token is associated with, and are commonly bought and sold on specialized marketplaces.

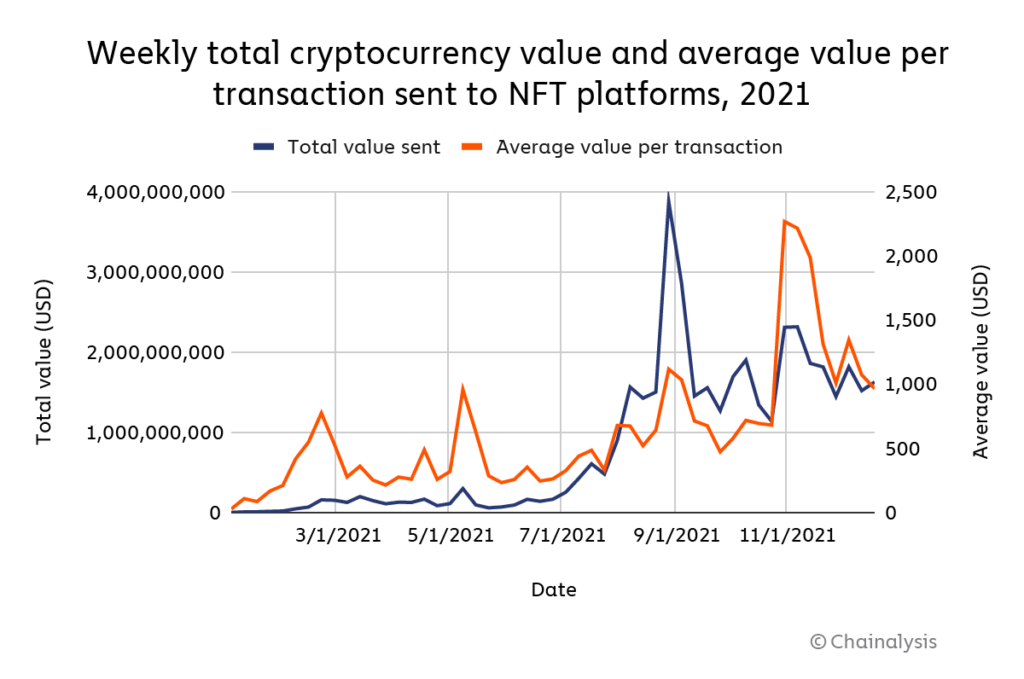

NFT popularity skyrocketed in 2021. Chainalysis tracked a minimum $44.2 billion worth of cryptocurrency sent to ERC-721 and ERC-1155 contracts — the two types of Ethereum smart contracts associated with NFT marketplaces and collections — up from just $106 million in 2020.

However, as is the case with any new technology, NFTs offer potential for abuse. It’s important that as our industry considers all the ways this new asset class can change how we link the blockchain to the physical world, we also build products that make NFT Weekly total cryptocurrency value and average value per transaction sent to NFT investment as safe and secure as possible. Below, we look at two forms of illicit activity we’ve observed in NFTs:

• Wash trading to artificially increase the value of NFTs

• Money laundering through the purchase of NFTs

Let’s dive in.

Some NFT sellers are making a killing with wash trading

Wash trading, meaning executing a transaction in which the seller is on both sides of the trade in order to paint a misleading picture of an asset’s value and liquidity, is another area of concern for NFTs. Wash trading has historically been a concern with cryptocurrency exchanges attempting to make their trading volumes appear greater than they are. In the case of NFT wash trading, the goal would be to make one’s NFT appear more valuable than it really is by “selling it” to a new wallet the original owner also controls. In theory, this would be relatively easy with NFTs, as many NFT trading platforms allow users to trade by simply connecting their wallet to the platform, with no need to identify themselves.

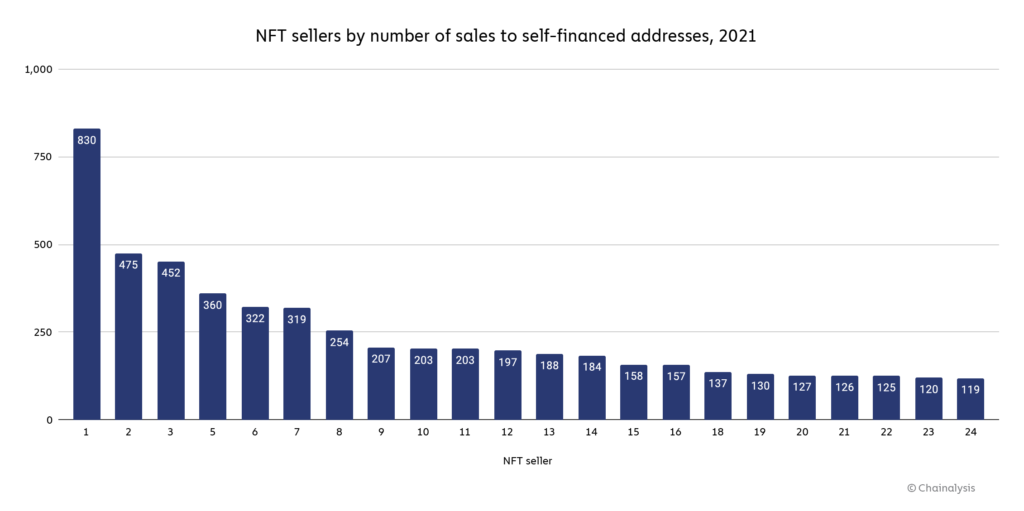

With blockchain analysis, however, we can track NFT wash trading by analyzing sales of NFTs to addresses that were self-financed, meaning they were funded either by the selling address or by the address that initially funded the selling address. Analysis of NFT sales to self-financed addresses shows that some NFT sellers have conducted hundreds of wash trades.

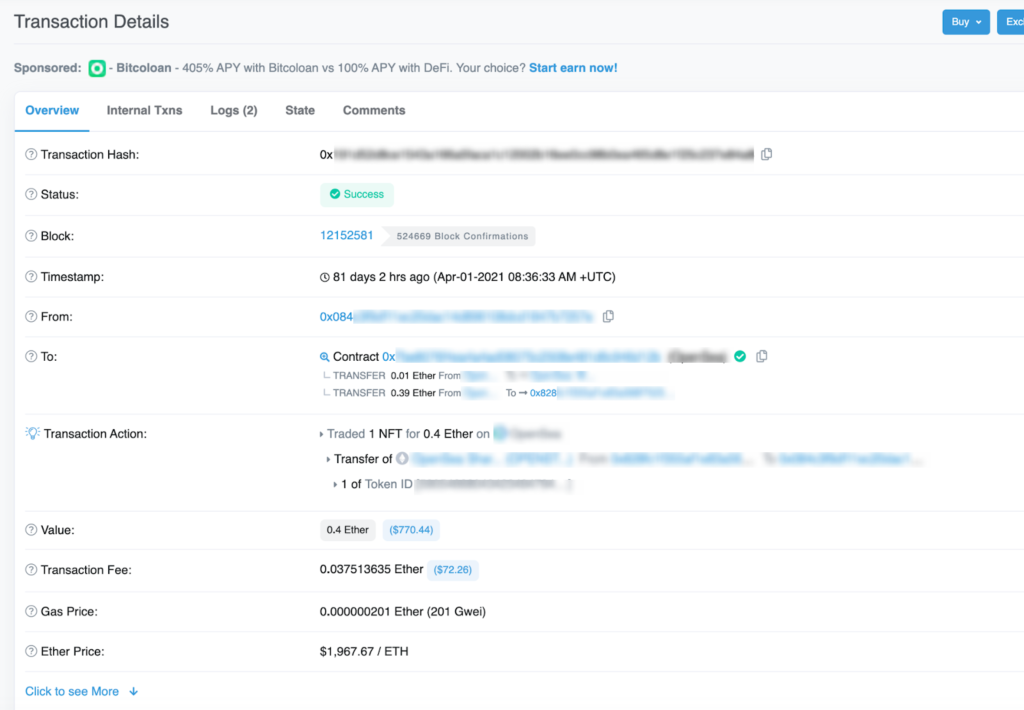

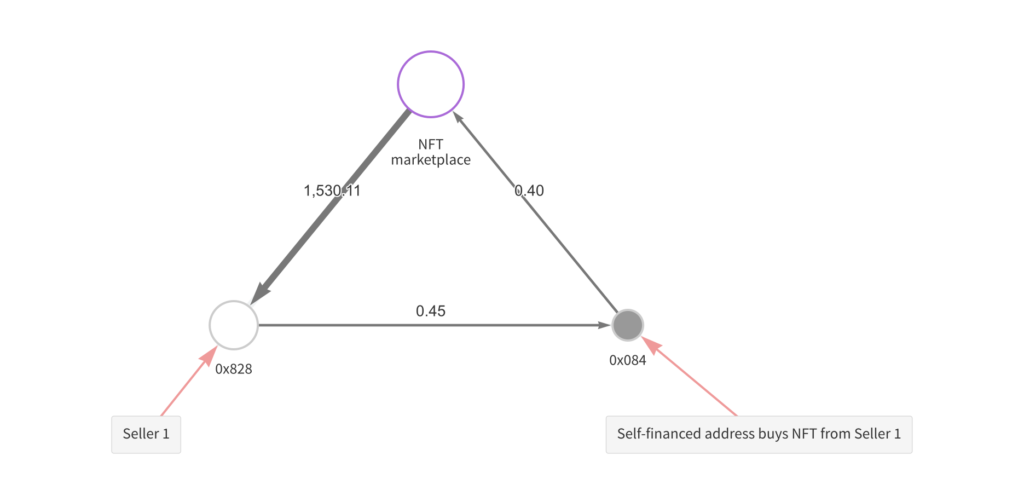

Let’s look more closely at Seller 1, the most prolific NFT wash trader on the chart above, who has made 830 sales to addresses they’ve self-financed. The Etherscan screenshot below shows a transaction in which that seller, using the address beginning 0x828, sold an NFT to the address beginning 0x084 for 0.4 Ethereum via an NFT marketplace.

Everything looks normal at first glance. However, the Chainalysis Reactor graph below shows that address 0x828 sent 0.45 Ethereum to that address 0x084 shortly before that sale.

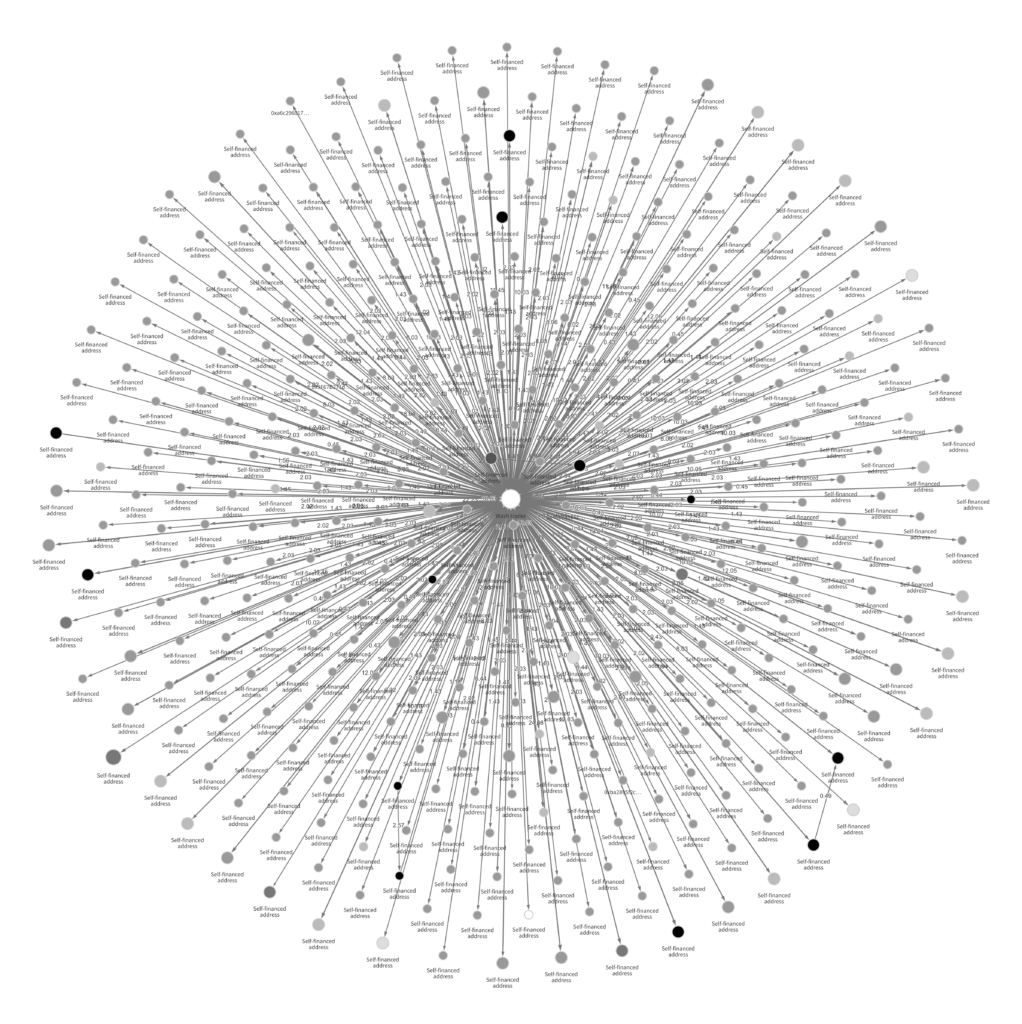

This activity fits a pattern for Seller 1. The Reactor graph below shows similar relationships between Seller 1 and hundreds of other addresses to which they’ve sold NFTs.

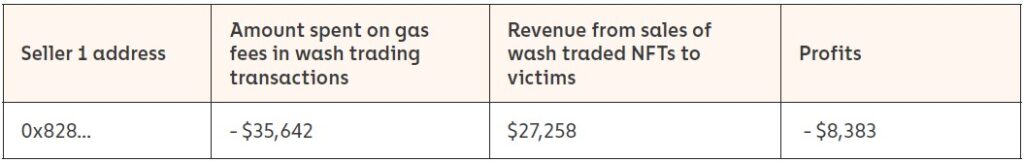

Seller 1 is the address in the middle. All other addresses on this graph received funds from Seller 1’s main address prior to buying an NFT from that address. So far though, Seller 1 doesn’t seem to have profited from their prolific wash trading. If we calculate the amount Seller 1 has made from NFT sales to addresses they themselves did not fund — whom we can assume are victims unaware that the NFTs they’re buying have been wash traded — it doesn’t make up for the amount they’ve had to spend on gas fees during wash trading transactions.

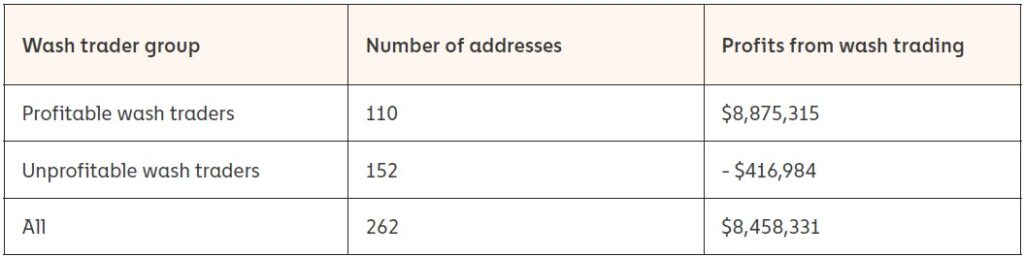

However, the story changes if we look at a bigger piece of the NFT ecosystem. Using blockchain analysis, we identified 262 users who have sold an NFT to a self-financed address more than 25 times. While we can’t be 100% sure that all instances of NFT sales to self-financed wallets are intended for wash trading, the 25-transaction threshold gives us a higher degree of confidence that these users are habitual wash traders. Just as we did above for one wash trader, we calculated these 262 wash traders’ overall profits by subtracting the amount they’ve spent on gas fees from the amount they’ve made selling NFTs to unsuspecting buyers. One caveat for this analysis is that it only captures trades made in Ethereum and Wrapped Ethereum, so there’s likely wash trading activity we’re not considering here.

Nonetheless, an interesting story emerges: Most NFT wash traders have been unprofitable, but the successful NFT wash traders have profited so much that, as a whole, this group of 262 has profited immensely overall.

The 110 profitable wash traders have collectively made nearly $8.9 million in profit from this activity, dwarfing the $416,984 in losses made by the 152 unprofitable wash traders. Even worse, that $8.9 million is most likely derived from sales to unsuspecting buyers who believe the NFT they’re purchasing has been growing in value, sold from one distinct collector to another.

NFT wash trading exists in a murky legal area. While wash trading is prohibited in conventional securities and futures, wash trading involving NFTs has yet to be the subject of an enforcement action. However, that could change as regulators shift focus and apply existing anti-fraud authorities to new NFT markets. More generally, wash trading in NFTs can create an unfair marketplace for those who purchase artificially inflated tokens, and its existence can undermine trust in the NFT ecosystem, inhibiting future growth. We encourage NFT marketplaces to discourage this activity as much as possible. Blockchain data and analysis makes it easy to spot users who sell NFTs to addresses they’ve self-financed, so marketplaces may want to consider bans or other penalties for the worst offenders.

Money laundering activity small but visible in NFTs

Money laundering has long been an issue in the fine art world, and it’s not hard to see why. As one 2019 article from the National Law Review points out, art pieces like paintings are easy to move, have relatively subjective prices, and may offer certain tax advantages. Criminals can therefore purchase art with illegally gained funds, sell them later, and poof — they have seemingly clean money with no connection to the original criminal activity. This background, along with the pseudonymity of cryptocurrency, has many wondering if NFTs are vulnerable to similar abuses. But while money laundering in physical art is difficult to quantify, we can make more reliable estimates of NFT-based money laundering thanks to the inherent transparency of the blockchain.

So, are cybercriminals using illicit funds to purchase NFTs? Let’s take a look.

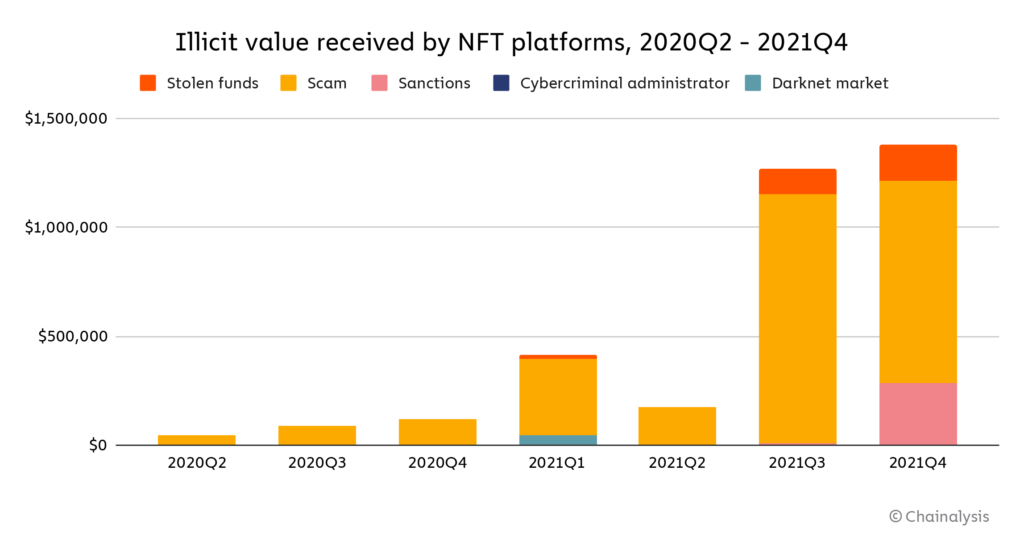

Value sent to NFT marketplaces by illicit addresses jumped significantly in the third quarter of 2021, crossing $1 million worth of cryptocurrency. The figure grew again in the fourth quarter, topping out at just under $1.4 million. In both quarters, the vast majority of this activity came from scam-associated addresses sending funds to NFT marketplaces to make purchases. Both quarters also saw significant amounts of stolen funds sent to marketplaces as well. Perhaps most concerningly, in the fourth quarter, we saw roughly $284,000 worth of cryptocurrency sent to NFT marketplaces from addresses with sanctions risk. All of that was due to transfers from the P2P exchange Chatex, which the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) added to its Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list last year.

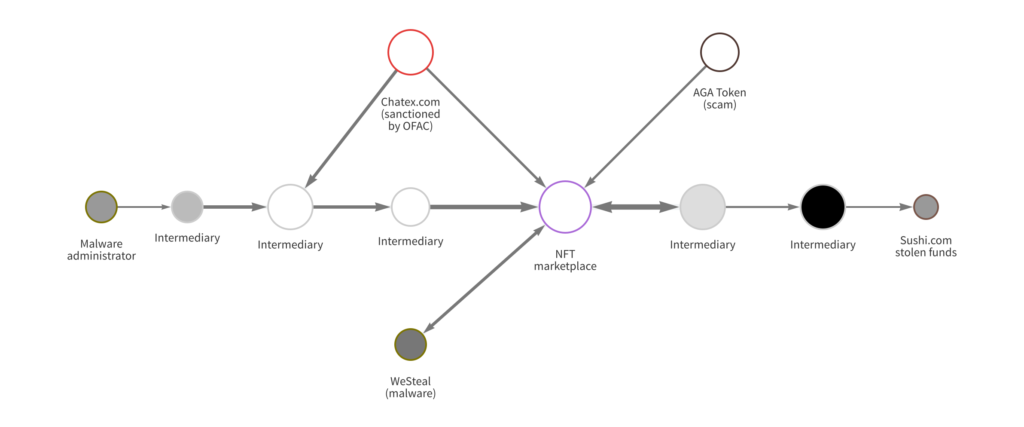

We can see examples of different types of criminals buying NFTs in the Reactor graph below.

Here, we can see addresses associated with several different types of cybercriminals interacting with a popular NFT marketplace, including malware operators, scammers, and Chatex.

All of this activity represents a drop in the bucket compared to the $8.6 billion worth of cryptocurrency-based money laundering we tracked in all of 2021. Nevertheless, money laundering, and in particular transfers from sanctioned cryptocurrency businesses, represents a large risk to building trust in NFTs, and should be monitored more closely by marketplaces, regulators, and law enforcement.